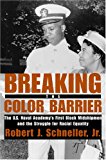

Extracted from Robert Schneller's (2005) The initial wave of African-American underclassmen faced a torrent of racism, ostracism, and physical brutality from their fellow classmates. In addition, the naval administration and political elites did little to shield the plebes from the daily onslaught. The official policy of the academy, outside of a brief few years during Reconstruction, was one of contempt and collusion in the attempts to run the African American plebes out of the Naval Academy. Schneller does a fine job of demonstrating the many dubious demerits that upperclassmen piled on the recruits, the fact that the Academy refused to give African Americans roommates, and the glaring social ostracism that they faced, especially from Southern white students. Other students viewed any attempt by a black plebe to stand up for himself as being "uppity," incurring wrath from classmates and disfavor from the naval administration. Schneller also notes that many of the first African-American plebes did have academic deficiencies in certain areas, caused largely by lack of educational opportunities for African Americans at the time, which lent cause to their dismissal (New York Press, 2005). An example of this was the case of James Conyers, who became the first black naval cadet in September 1872. Hailing from South Carolina, Conyers received nomination from Robert Elliot, a South Carolina congressman. Conyers' first year at the academy was marked by unceasing verbal torment, seclusion, beatings and an attempted drowning by his classmates, among other abuses. Conyers yielded to the academic, physical, and psychic pressures and resigned by October 1873. Over the years, the next four African-American cadets faced parallel pressure and similarly bowed out after their freshman year. Altering this environment took many years and came from several different directions. Many changes occurred before the Naval Academy's first successful black midshipman, Wesley Brown. One was ongoing pressure by African-American political figures in the 1930s and 1940s. The increased social and ethnic diversity of incoming classes during the same time period also allowed for more tolerance and acceptance. As Schneller argues though, nothing made a bigger impact than the fundamental shift in official naval policy required by the demands of World War II. The vast increase in demand for manpower that the navy needed to fight in Europe and the Pacific called for a much more inclusive policy, one that would accept all recruits regardless of race. Wesley Brown, a Washington D.C. native, came into the Naval Academy in 1945 on a nomination by Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a congressman from Harlem, who was perhaps the most powerful and influential African-American politician of the twentieth century. Bright, athletic, likable, and deeply driven, Brown went to Annapolis in the summer of 1945 knowing he would face major obstacles but determined to overcome them. At the academy, he found that several dozen upperclassmen were bent on driving him out by giving him an overload of demerits. What the book shows is that unlike previous black plebes, he not only had administrative support, but more directly the support of a number of fellow white plebes and upperclassmen, including a future president of the United States, Jimmy Carter. Once he survived his plebe year, Brown found that his next three years, although extremely challenging, were comparatively easy and relatively quick. By the time he graduated in 1949, becoming the first commissioned black officer in the Navy, Brown's stature within his community rivaled that of Joe Louis and Jesse Owens. African Americans had broken through another barrier and, though the author does not state it, one could almost hear the Civil Rights movement marching around the corner. Like previous black recruits, Brown did not have a roommate his first year. By 1972 the isolation of Black midshipmen had ended maybe because the numbers prevented such action. I was lucky to have a Black upper class midshipmen in the 17th Company. The Class of 1973 had only 12 Black graduates. Reference Robert J. Schneller, Jr. Breaking the Color Barrier: The U.S. Naval Academy's First Black Midshipmen and the Struggle for Racial Equality. New York: New York University Press, 2005. xii + 331 pp. $34.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8147-4013-2.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Dr. Jordan B smith jr.I attended the U. S. Naval Academy from 1972-1976 earning a B.S. in Mathematics. Served 20 years both active and reserve in the US Marines. Veteran of the Desert Shield/Storm. I earned a MAED and Ed D. specializing in curriculum and instruction from the University of Phoenix in 2015. I graduated from CBC High School in Clayton, MO in 1972. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed